How Evolution Made Baby-faced Humans & Adorable Dogs

Who among us hasn’t looked at the big round eyes of a child or a puppy gazing up at us and wished that they’d always stay young and cute like that? You might be surprised to know that this wish has already been partially granted. Both you as an adult and your full-grown dog are examples of what’s referred to in developmental biology as paedomorphosis (“pee-doh-mor-fo-sis”), or the retention of juvenile traits into adulthood. Compared to closely related and ancestral species, both humans and dogs look a bit like overgrown children. There are a number of interesting reasons this can happen. Let’s start with dogs.

When dogs were domesticated, humans began to breed them with an eye to minimizing the aggression that naturally exists in wolves. Dogs that retained the puppy-like quality of being unaggressive and playful were preferentially bred. This caused certain other traits associated with juvenile wolves to appear, including shorter snouts, wider heads, bigger eyes, floppy ears, and tail wagging. (For anyone who’s interested in a technical explanation of how traits can be linked like this, here’s a primer on linkage disequilibrium from Discover. It’s a slightly tricky, but very interesting concept.) All of these are seen in young wolves, but disappear as the animal matures. Domesticated dogs, however, will retain these characteristics throughout their lives. What began as a mere by-product of wanting non-aggressive dogs has now been reinforced for its own sake, however. We love dogs that look cute and puppy-like, and are now breeding for that very trait, which can cause it to be carried to extremes, as in breeds such as the Cavalier King Charles spaniel, leading to breed-wide health problems.

Foxes, another type of wild dog, have been experimentally domesticated by scientists interested in the genetics of domestication. Here, too, as the foxes are bred over numerous generations to be friendlier and less aggressive, individuals with floppy ears and wagging tails – traits not usually seen in adult foxes – are beginning to appear.

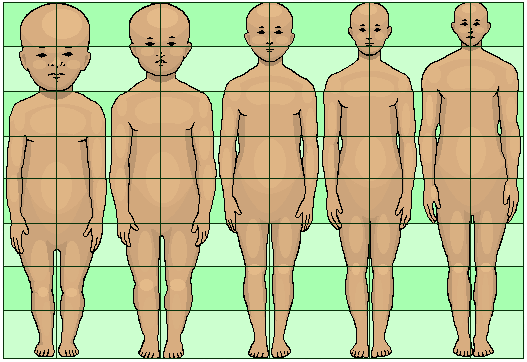

But I mentioned this happening in humans, too, didn’t I? Well, similarly to how dogs resemble juvenile versions of their closest wild relative, humans bear a certain resemblance to juvenile chimpanzees. Like young apes, we possess flat faces with small jaws, sparse body hair, and relatively short arms. Scientists aren’t entirely sure what caused paedomorphosis in humans, but there are a couple of interesting theories. One is that, because our brains are best able to learn new skills prior to maturity (you can’t teach an old ape new tricks, I guess), delayed maturity, and the suite of traits that come with it, allowed greater learning and was therefore favoured by evolution. Another possibility has to do with the fact that juvenile traits – the same ones that make babies seem so cute and cuddly – have been shown to elicit more helping behaviour from others. So the more subtly “baby-like” a person looks, the more help and altruistic behaviour they’re likely to get from those around them. Since this kind of help can contribute to survival, it became selected for.

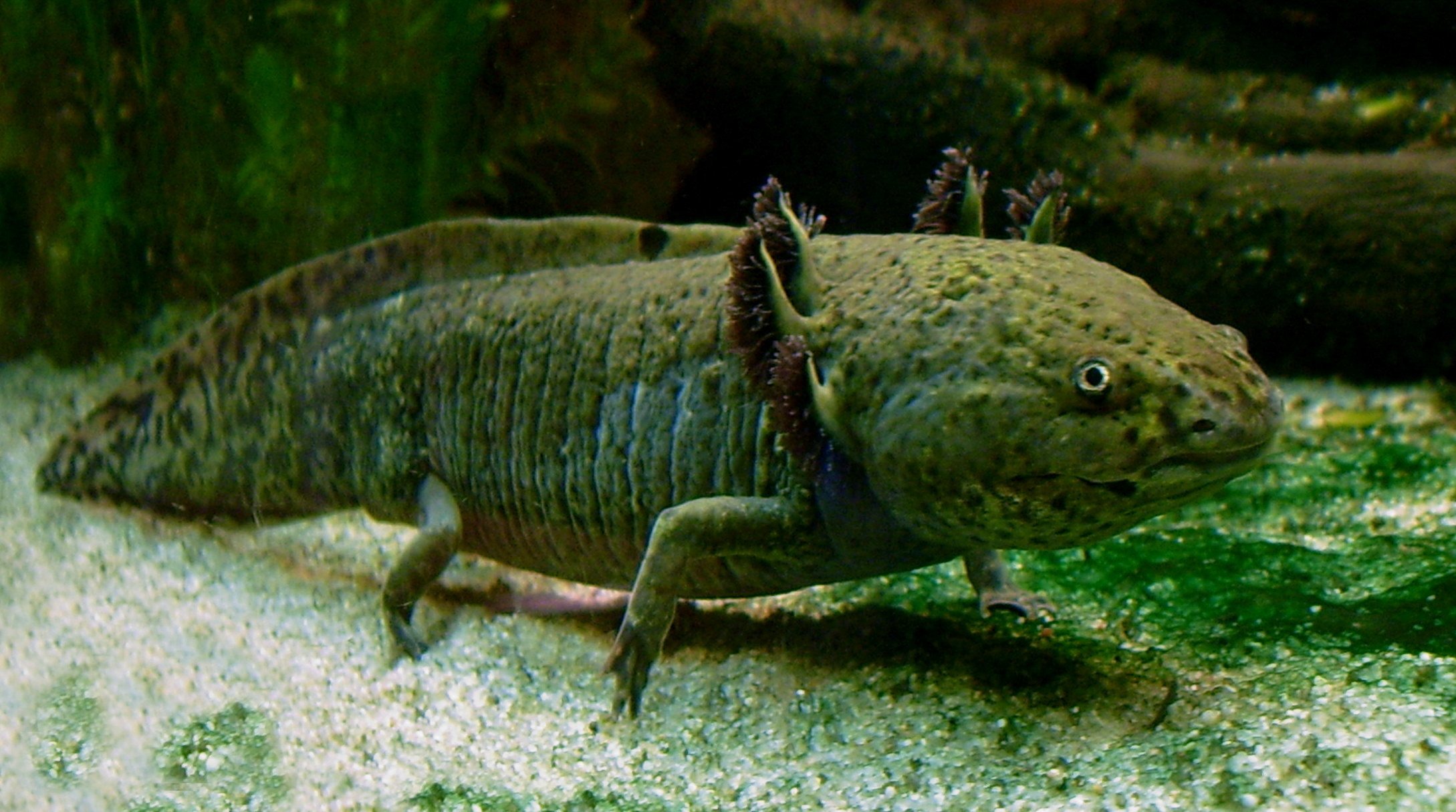

Of course, dogs and humans aren’t the only animals to exhibit paedomorphosis. In nature, the phenomenon is usually linked to the availability of food or other resources. Interestingly, both abundance and scarcity can be the cause. Aphids, for example, are a small insect that sucks sap out of plants as a food source. Under competitive conditions in which food is scarce, the insects possess wings and are able to travel in search of new food sources. When food is abundant, however, travel is unnecessary and wingless young are produced which grow into adulthood still resembling juveniles. Paedomorphosis is here induced by abundant food. Conversely, in some salamanders, it is brought on by a lack of food. Northwestern salamanders are typically amphibious as juveniles and terrestrial as adults, having lost their gills. In high elevations where the climate is cooler and a meal is harder to come by, many of these salamanders remain amphibious, keeping their gills throughout their lives because aquatic environments represent a greater chance for survival. In one salamander species, the axolotl (which we’ve discussed on this blog before), metamorphosis has been lost completely, leaving them fully aquatic and looking more like weird leggy fish than true salamanders.

So paedomorphosis, this strange phenomenon of retaining juvenile traits into adulthood, can be induced by a variety of factors, but it’s a nice demonstration of the plasticity of developmental programs in living creatures. Maturation isn’t always a simple trip from point A to point B in a set amount of time. There are many, many genes at play, and if nature can tweak some of them for a better outcome, evolution will ensure that the change sticks around.

Sources

- Martin & Gordon (1995) Journal of Evolutionary Biology 8:339-354

- Trut (1999) American Scientist 87(2):160-169.

- Trut et al. (2009). BioEssays 31:349-360.

- Waller et al. (2013) PLoS ONE 8(12): e82686.

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/being-more-infantile/

*Header image by: Ephert – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39752841

Try to imagine a colour you’ve never seen. Or a scent you’ve never smelled. Try to picture the mental image produced when a bat uses echolocation, or a dolphin uses electrolocation. It’s nearly impossible to do without referring to a previous experience, or one of our other senses. We tend to tacitly assume that what we perceive of the world is more or less all there is to perceive. It would be closer to the truth to say that what we perceive is what we need to perceive. Humans don’t require the extraordinary sense of smell that wild dogs do in order to get by in the world. But it wasn’t always this way.

Try to imagine a colour you’ve never seen. Or a scent you’ve never smelled. Try to picture the mental image produced when a bat uses echolocation, or a dolphin uses electrolocation. It’s nearly impossible to do without referring to a previous experience, or one of our other senses. We tend to tacitly assume that what we perceive of the world is more or less all there is to perceive. It would be closer to the truth to say that what we perceive is what we need to perceive. Humans don’t require the extraordinary sense of smell that wild dogs do in order to get by in the world. But it wasn’t always this way.